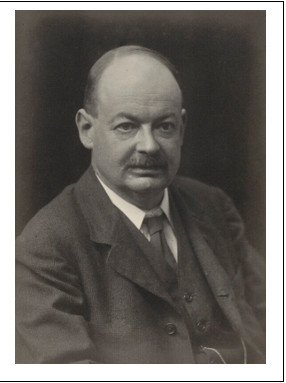

Time Lord No. 1: John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart

In 1908, a Cambridge philosopher published a paper with a title that still has the power to unsettle anyone who pauses long enough to consider it: The Unreality of Time.

More than a century later, philosophers are still arguing with him. For this alone, John McTaggart Ellis McTaggart earns the title of my first Time Lord.

McTaggart (known to his colleagues simply as “McT”) was born in London in 1866 and spent most of his career at Cambridge. He was a British Idealist influenced deeply by Hegel, and he believed that ultimate reality consists not of material objects but of minds and the relations between them. His broader metaphysical work focused heavily on Hegel, mysticism, and the structure of existence. But it is his argument about time that detonated a conceptual bomb still echoing today.

But before we get to that bomb, here’s a bit of color.

McTaggart was by all accounts an eccentric. He reportedly shuffled along corridors with his back to the wall, as if expecting a sudden kick from behind. He saluted passing cats. He rode a tricycle around Cambridge, inspiring a local poem:

Philosopher, your head is all askew;

Your gait is not majestic in the least;

You ride three wheels, where other men ride two;

Philosopher, you are a funny beast.

He was apparently delighted by this. I admit, I too, find that endearing. But whatever one thought of his quirks, no one doubted his intellect. McTaggart is regarded as one of the most important metaphysicians of the twentieth century. And in 1908, in the journal Mind, he published the paper that secured his philosophical immortality.

The A-Series and the B-Series

McTaggart began with a deceptively simple observation: if time is real, it must involve some sort of ordering of events. The question is — what kind of ordering? He proposed that there are two fundamentally different ways to order events in time. He called them the A-series and the B-series.

The A-series orders events as past, present, and future. According to this view, events genuinely change their temporal status. A future event becomes present, and then becomes past. This is how we ordinarily experience time. We speak of time flowing, of moments passing, of the “now” advancing.

The B-series, by contrast, orders events as earlier than, later than, or simultaneous with other events. In this view, the relations between events do not change. Mother’s Day 2021 is always later than Mother’s Day 2020 and earlier than Mother’s Day 2022. Those relations are fixed. There is no moving “now.” There is simply a network of temporal relations.

So far, this might seem like two different descriptions of the same thing. McTaggart insisted they are not.

And here is where the bomb goes off.

He claimed that genuine change requires the A-series. For time to pass, events must move from future to present to past. Without that movement, there is no real change, only a static ordering. But then he argued that even so, the A-series is internally contradictory!

Why?

Because every event must be either past, present, or future — and cannot be more than one at the same time. Yet every event seems to possess all three characteristics. If an event is present, it was future and will be past. If it is past, it was once present and future. Every event appears to have all three properties.

McTaggart concluded that this involves a contradiction. If the A-series is contradictory, and if time requires the A-series, then time itself cannot be real.

The B-series, meanwhile, avoids contradiction — but at a cost. According to McTaggart, it cannot account for genuine change. Relations like “earlier than” never change. The timeline, on the B-series, is static.

Thus, he rejected both. And from this, he drew the astonishing conclusion:

Time is unreal.

After the Explosion

Philosophy has been responding to McTaggart ever since.

Later thinkers refined his categories into now familiar positions in contemporary debates:

- Presentism

- The growing block universe

- Eternalism

- Four-dimensionalism

Nearly every serious discussion of the metaphysics of time still traces back to his A/B distinction.

Was he right?

I don’t know, but I must confess that I am not yet prepared to declare time unreal. My knees are barking their disagreement. Whether one agrees with him or not, McTaggart forced philosophers to confront something unsettling: the possibility that our most basic intuition — that time flows — might not withstand scrutiny.

At seventy-five, this is not an abstract puzzle for me. Time is something I feel. It marks my calendar and my body. And yet here stands a tricycle-riding metaphysician from 1908 calmly arguing that the whole thing is bogus.

That’s not a footnote. That’s a detonation.

Mind.Blown.

Welcome to my first Time Lord.