[Note: I wrote this paper in 2017 as the final assignment in my “Intro to Philosophy of Mind” class. It is meant to be “introductory”, so it is very high-level.]

Getting a Grip On Reality: Towards a Holistic Ontology

From the ancient Greeks to the present day, philosophers have been seeking to understand and explain the nature of human consciousness. Many, if not most, of the theories of consciousness proposed and explored from the very beginning have placed an emphasis on finding consciousness either outside of our body, yet somehow connected to it, as the dualists purport; or within our brains, as evidenced by brain functions by the physicalists. To date, research conducted to support or refute both of these traditional approaches to what is commonly referred to as “the mind-body problem”, has resulted in expanding our knowledge of the physical inner-workings our brains, what David Chalmers has referred to as “the easy problems”. But so far neither approach has been able to explain what Chalmers refers to as “the hard problem” – the problem of experience i.e., “It is widely agreed that experience arises from a physical basis, but we have no good explanation of why and how it so arises. Why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life at all? It seems objectively unreasonable that it should, and yet it does.”[1]

Indeed, the years and philosophical effort put into arguing these two opposing points of view have left little room for new ideas, new approaches to the mind-body problem, and have not done much to explain our ability to experience anything. I think that so far the two traditional approaches to the mind-body problem have resulted in philosophers playing the part of blind men in the old parable: “…a group of blind men (or men in the dark) who touch an elephant to learn what it is like. Each one feels a different part, but only one part, such as the side or the tusk.”[2] In fact, the two traditional approaches have led to further struggles in trying to define the relationship between self and the world, between subject and object, and perception itself. Thus, I believe there is a fundamental flaw with both of these traditional approaches and that it is time for something different; an approach to the problem that includes a broader description of consciousness, one that begins with the embodiment of consciousness by a subject who, from the very beginning, is “in the world”, a world that is immediately available to that subject through their perception.

While certainly different from the traditional dualist or physicalist theories, I cannot claim that the theory I am supporting encompassing embodiment, being “in the world”, is new, for it is not. Phenomenologists such as Heidegger, Edmund Husserl and Merleau-Ponty presented and argued many of these points years ago and today others such as Alva Noe and David Chalmers are standing on the shoulders of these giants as they attempt to lead all of us in a new direction, to the adoption of a new paradigm for the philosophy of mind. I will not be embracing any discussion on the traditional dualist theories in this paper because there is not a single thread of evidence to support them. Nor will I attempt to defend any physicalist theory. Instead, my purpose in this very brief paper is simple – to describe this new paradigm by explaining some of the key thinkers and purveyors of what I am calling the new paradigm i.e., Husserl, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Alva Noe, and David Chalmers.

There is an old adage that claims “you cannot see the forest for the trees”. It’s a pejorative statement really, one that implies you are lost in the details and missing the bigger picture. I think this is a claim that applies to much of the historical research done in the philosophy of mind. Once you rule out God and the existence of invisible ethereal essences (the dualist perspective), it is only natural to immediately look at our brain when trying to understand what consciousness is all about (the physicalist perspective). By doing so, however, instead of stepping back and looking at the “bigger picture”, philosophers and scientists alike became immersed in detailed cause and effect analyses. Consciousness, viewed as an effect, resulted in much research into the probable physical causes of such an amazing phenomenon. It is arguable as to why this particular rabbit hole occurred, perhaps because philosophers and scientists, who were once one in the same, are just nerdy, technical people; but I believe that early on it irrefutably led to limit the focus of research, to narrow the questions asked and answered, and framed the mind-body problem in such a way that the only tools and methods considered worthy of use and therefore acceptable, were tools based on a physicalist point of view.

There is no need (nor space) here to recount the brilliant ways in which Chalmers explains how physicalist theories in the end only describe brain functions and have no explanation for experience. These physicalist theories, of course, are all based on a similar set of ideas, a similar perspective, which is the essential definition of a “paradigm”, a paradigm that has been in use for a very long time. The problem with paradigms is, unfortunately, that once they become adopted they are extremely hard to break. In this, paradigms are like old habits, which I believe deserves some attention.

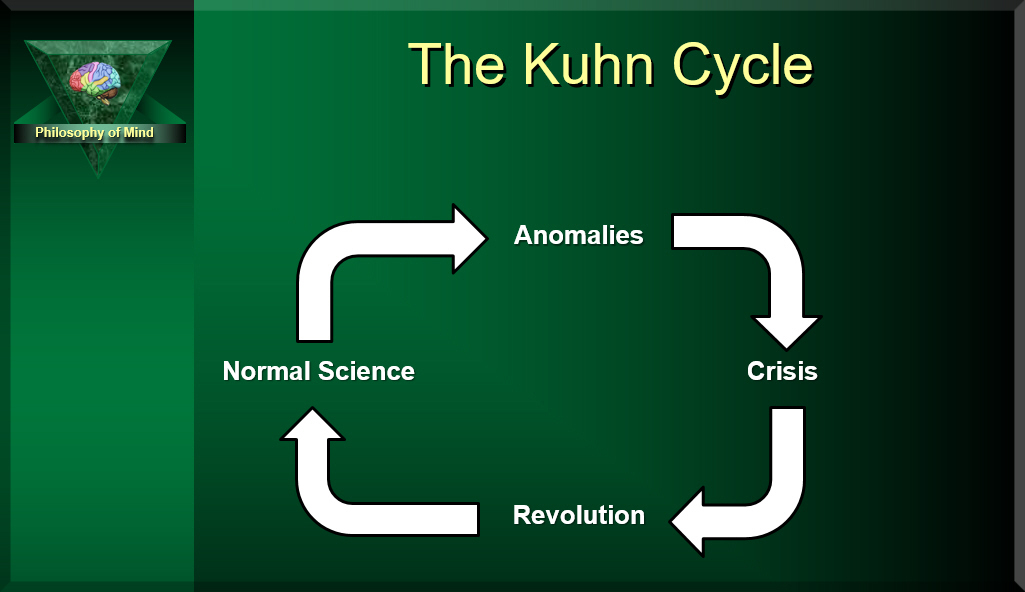

Philosophy of Science professor, Thomas Kuhn, wrote a book called, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In it, Kuhn describes how historically-entrenched scientific paradigms eventually get changed, something he calls a paradigm shift[3]. In his book, Kuhn describes a progression of events others refer to as the “Kuhn Cycle”, which looks like graphic-1 below.

Graphic-1

Graphic-1

To explain – inevitably almost all scientific theories (normal science) include some anomalies. These anomalies don’t seem to matter much to the scientists who adhere to a specific paradigm. Over time however, things can change and the anomalies begin to increase in number and/or importance and eventually reach a point where the accepted paradigm that provided good and acceptable answers no longer does the job and this eventually leads to a crisis. Kuhn has much to say on this subject and I can’t cover it all here, but let it suffice to say that new problems that no longer can be addressed by the current paradigm; new questions that cannot be answered by the current paradigm; and tools that no longer provide acceptable results based on the current paradigm, cause a crisis to occur within the scientific community that has been laboring under the auspices of the current paradigm. This is often caused by a new, competing paradigm that has appeared on the scene. But, if no new paradigm is handy, people then search for a new, better solution, and when a solution has been found we have what Kuhn called a paradigm shift, the situation that occurs as people change from the old paradigm to the new paradigm. And when a paradigm shift occurs, we have what Kuhn calls a scientific revolution.

I believe that the field of the philosophy of mind is currently somewhere between anomalies and crisis and is well on its way through a paradigm shift, and if this doesn’t describe the current state of the field, I believe that a crisis is needed and I can’t help but hope that it comes soon.

To have a crisis in the philosophy of mind and herald in a paradigm shift, the current accepted paradigm – the physicalist perspective – must be successfully challenged and evidence uncovered that provides sufficient cause for adherents to recognize its failings, so they can begin to reject it. The work of celebrated philosophers such as Chalmers and Noe demands that a new perspective, a new non-physicalist paradigm be found. This new paradigm hasn’t exactly been defined yet, but their work is causing philosophers to reconsider the veracity of the physicalist paradigm; forcing us to revisit the initial context of the mind-body problem itself; to ask new questions within a philosophical framework that includes something that might be called radical – a basic appeal to common sense. As Kuhn points out in his book, some people will accept the new paradigm, others will eventually be swayed to accept the new paradigm, while still others will reject the new paradigm outright and as has been demonstrated in scientific experiments, some paradigm-deniers often cannot even physically see the new paradigm – such is the psychological strength of an existing paradigm!

Although the way in which Noe and Chalmers talk about the new paradigm for philosophy of mind – one that begins with the common sense given that consciousness is always consciousness of something, that we exist from the get-go in a physical world populated by other conscious beings – may sound new to some, it is actually being built on ideas that have been around for years, with its origin in the realm of phenomenology[4] and takes full advantage of the great phenomenologists of our time – Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) is often called the “father of phenomenology”. The philosophies that influenced him the most were from Descartes, Hume, and Kant[5]. It is believed that it was after reading Descartes’ Meditations when Husserl considered the possibility of seeking a universally rational “science of being” (proposed by Heidegger) by turning his theoretical focus from an objective world to a reflective world, one where “phenomenology is “the reflective study of the essence of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view.”[6] Was Husserl moved by Descartes’ “Cogito ergo sum”? I’d say so. Who isn’t?

Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) is often called the “father of phenomenology”. The philosophies that influenced him the most were from Descartes, Hume, and Kant[5]. It is believed that it was after reading Descartes’ Meditations when Husserl considered the possibility of seeking a universally rational “science of being” (proposed by Heidegger) by turning his theoretical focus from an objective world to a reflective world, one where “phenomenology is “the reflective study of the essence of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view.”[6] Was Husserl moved by Descartes’ “Cogito ergo sum”? I’d say so. Who isn’t?

Husserl’s approach in the early 20th century was radical indeed and attempted to turn the philosophy of mind community on its head by bringing consciousness itself, subjectivity itself, that which physicalist have always struggled with, out of the shadows and into the light of center stage. He was not interested in metaphysics per se, espousing that only through consciousness itself could we find the meaning behind behavior[7]. He also explored our ability to perceive the world and by so doing, elevated the concept of perception itself within philosophy of mind, forcing many to question our experience of reality. There is, I believe, a reason this phenomenological attitude has gradually, but steadily been gaining ground over the years and it may be as simple as the appeal to common sense, for in many ways it is the manner in which all of us experience the world.

Husserl by himself, is too big a subject for me to cover appropriately here, but I do believe his attitude, his foresight and his phenomenology formed the basis of the current movement, if it can be called a movement, pursuing the new paradigm I am describing for philosophy of mind. Husserl turned his attention in many different related directions during the course of his life and work, some of which were rejected by his peers (e.g., his adoption of transcendence[8]), while other ideas were adopted and massaged as we shall see below (e.g., intersubjectivity[9] and intentionality[10], embodiment[11]), yet some adherents seized upon his brilliance and used it as a virtual atlatl[12] to take the philosophy of mind further in a new direction. One such person was Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) was a student of Edmund Husserl. He attended Husserl’s 1929 Sorbonne lectures[13] and was the first student to study at the Husserl archives in Leuven, Belgium. Merleau-Ponty rejected reductionism: “The most important lesson that the reduction teaches us…is the impossibility of a complete reduction”[14], and also rejected his teacher’s belief in transcendence. What Merleau-Ponty did do however, is take perception and its place in phenomenology to an entirely new level. Merleau-Ponty rooted his ideas about perception not just in the real world, but where it belongs – in our bodies: “Our own body is in the world as a heart is in the organism: it keeps the visible spectacle constantly alive, it breathes life into it and sustains it inwardly, and with it forms a system.”[15] Embodiment, sometimes called embodied perception, is at the heart of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology and he makes a point of stating the primacy of perception, which was also the title on a collection of his articles.[16] Intentionality is another subject Merleau-Ponty adopted and advanced, the spirit of which was certainly captured in his famous statement, “Consciousness is always consciousness of something.”[17] And we mustn’t forget intersubjectivity – Merleau-Ponty tells us that we live in an intersubjective world, one that is populated with our self and a plurality of – gasp – other subjects, who are in turn, experiencing their self and others. He expands on this beyond anything I can cover here, but there is a something about Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology that has always struck me as real, if that makes sense. Couched in lofty terms and wonderful, albeit complex concepts, it has always seemed to me to be more down to earth than others who have broached the subject.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) was a student of Edmund Husserl. He attended Husserl’s 1929 Sorbonne lectures[13] and was the first student to study at the Husserl archives in Leuven, Belgium. Merleau-Ponty rejected reductionism: “The most important lesson that the reduction teaches us…is the impossibility of a complete reduction”[14], and also rejected his teacher’s belief in transcendence. What Merleau-Ponty did do however, is take perception and its place in phenomenology to an entirely new level. Merleau-Ponty rooted his ideas about perception not just in the real world, but where it belongs – in our bodies: “Our own body is in the world as a heart is in the organism: it keeps the visible spectacle constantly alive, it breathes life into it and sustains it inwardly, and with it forms a system.”[15] Embodiment, sometimes called embodied perception, is at the heart of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology and he makes a point of stating the primacy of perception, which was also the title on a collection of his articles.[16] Intentionality is another subject Merleau-Ponty adopted and advanced, the spirit of which was certainly captured in his famous statement, “Consciousness is always consciousness of something.”[17] And we mustn’t forget intersubjectivity – Merleau-Ponty tells us that we live in an intersubjective world, one that is populated with our self and a plurality of – gasp – other subjects, who are in turn, experiencing their self and others. He expands on this beyond anything I can cover here, but there is a something about Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology that has always struck me as real, if that makes sense. Couched in lofty terms and wonderful, albeit complex concepts, it has always seemed to me to be more down to earth than others who have broached the subject.

Merleau-Ponty believed that human cognition (awareness) and movement were emergent properties, the result of the interaction between a biological system (our bodies) and an environment (the world). He believed that human experience itself was not just spatially extended (in the world), but also temporally extended (in time). In other words, he posits the initial context for solving the mind-body problem as an embodied mind perceiving a physical world, populated in a social setting with other conscious people, which is exactly the way each and every one of us experiences anything, if you think about it for a moment. For Merleau-Ponty, the embodied consciousness was fundamental. I can’t help but emphasize terms like embodiment, emergent properties, or fundamental enough, because these are, I think, the three legs of the new philosophy of mind paradigm, as espoused by two more modern philosophers, Alva Noe and David Chalmers, who have continued to build on the foundation laid by both Husserl and Merleau-Ponty.

Alva Noe (1964 -) is a University of Berkeley philosophy professor. His area of study is perception and consciousness and he is also involved in cognitive science, the philosophy of mind and phenomenology.[18]

Alva Noe (1964 -) is a University of Berkeley philosophy professor. His area of study is perception and consciousness and he is also involved in cognitive science, the philosophy of mind and phenomenology.[18]

Noe, like Merleau-Ponty, believes that to understand consciousness, we have to consider more than just our brains. He states, “Consciousness does not happen in the brain”[19] He doesn’t deny the importance of that lump of gray matter between our ears, but tells us that if we want to really understand consciousness we have to look at consciousness as the result of the interaction between our bodies and the world it inhabits.[20] It is arguable whether Noe succeeds in ever defining consciousness itself, but he is definitely singing out of the new paradigm hymnal – we are embodied minds in a physical world populated with other conscious creatures and if we ever hope to understand consciousness, we have to step back, catch our breath, and take a wider view of the whole organism interacting with its environment.[21] He tells us that if we want to get some insight into the nature of consciousness, we just need to look at the connections between ourselves and our environment, nature, and other people. Doing so, will give us the tools we need to figure it out. For Noe, consciousness isn’t something to be found inside of us, it is something we do, which interestingly, makes consciousness more of a verb than a noun.

Last, but not least, there is David Chalmers (1966 -). Chalmers is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist specializing in philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. Chalmers is also the director for the Centre of Consciousness at the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia. Chalmers is, of course, the man who defined what is now commonly referred to as the hard problem for philosophy of mind, which is the problem of experience i.e., “Why does the feeling which accompanies awareness of sensory information exist at all?”[22] What are the easy problems? Those are all the problems having to do with functions which are theoretically answerable through normal science, ongoing research and of course, by functionalism itself.

Last, but not least, there is David Chalmers (1966 -). Chalmers is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist specializing in philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. Chalmers is also the director for the Centre of Consciousness at the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia. Chalmers is, of course, the man who defined what is now commonly referred to as the hard problem for philosophy of mind, which is the problem of experience i.e., “Why does the feeling which accompanies awareness of sensory information exist at all?”[22] What are the easy problems? Those are all the problems having to do with functions which are theoretically answerable through normal science, ongoing research and of course, by functionalism itself.

I include Chalmers as someone who is driving the field towards the new philosophy of mind paradigm for several reasons. His work is avant garde to say the least, which is reminiscent to me of Merleau-Ponti. Like the others mentioned above, Chalmers starts with a given – a conscious being in a populated world containing other conscious beings all of whom are experiencing the world and each other through the immediacy of their perception. Sound familiar? Chalmers however, does not rest on his laurels and instead is trying to steer the field in some very interesting, but somewhat different, directions than his predecessors.

He destroys functionalism with what might be described as laser beam logic, the kind that leaves you thinking, “Wow, of course. Why didn’t I see that?” Similar to Alva Noe, Chalmers talks about extended cognition, which is what happens when objects within an environment function as part of a mind. To Chalmers, the separation between mind, body and the environment is an unprincipled distinction.[23] The fact that external objects play such an important role in aiding our cognitive processes, means that “the mind and the environment act as a ‘coupled system.’”[24]

I haven’t yet had a chance to dive very deep into the system concept discussed by Chalmers, but have made note that terms like system and process are being used by Merleau-Ponty, Noe and Chalmers in conjunction with their theories. I suspect that this is more than just a sign of the times and that whenever the new philosophy of mind paradigm is defined, it will include the use of such terms. They are more than descriptive. They help expand the grasp of what is possible.

Chalmers again pushes the envelope by adopting a rather clever form of dualism, sometimes called property dualism[25], although Chalmers calls it naturalistic dualism. Unlike traditional dualism that involves two distinct substances, one physical, the other ethereal, Chalmers believes that his dualism is naturalistic because although mental states are in fact caused by physical systems (like the brain), the mental states themselves “are ontologically distinct from and not reducible to physical systems”[26]. In this sense, he is a non-reductionist.

Chalmers doesn’t stop there. For Chalmers, consciousness is fundamental, like the law of gravity. Declaring consciousness as ontologically autonomous of any physical properties, he thinks there may be psychophysical laws that determine which physical systems are associated with different types of qualia. And still Chalmers is not yet done. He also believes that advanced information-bearing systems may be conscious! And wait, there’s more! Going even further out on a limb, Chalmers is also entertaining the possibility of pansychism! Unlike the common definition of panpsychism which essentially believes that everything has a mind, Chalmers is purporting only (only?) that some fundamental physical entities may be conscious.[27] He admits that this theory puts him at odds with many, if not most, of his contemporaries, but like the philosophical pioneer that he is, he’s throwing the idea into the mix just to see what shakes out.

One of the things that I really like about Chalmers’ ideas about consciousness is that everything he puts forward can potentially be figured out by science and research. Even his naturalistic dualism theory, unlike the traditional dualist theory where one entire side of the equation was out of bounds for any scientific research, Chalmers’ dualist theory leaves an opening for research and the scientific method to delve into it further and get to the bottom of it. There is no hokus-pokus to it, there are just scientific facts that we haven’t discovered yet.

I hope that this brief paper has provided some support for my belief that the traditional philosophy of mind paradigm based on physicalism, which is still supported by many in the field, should eventually be retired and replaced by a phenomenological theory of consciousness that is – to borrow a term used by Chalmers – naturalistic – but also holistic (the embodiment or fusion of mind and body), in that it begins by getting a grip on the reality we all experience everyday – that of conscious beings interacting with the physical world while surrounded by other conscious beings who are doing the same thing. I also hope that I explained enough of the new paradigm for the philosophy of mind to make you at least ponder the possibility.

Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Noe and Chalmers all have one thing in common – they are disruptors, change agents for the philosophy of mind; asking old questions that require new thinking to find answers; asking new questions that make us rethink our long-held positions; dreaming up new tools to solve both old and new problems. Hopefully, they are all bringing us closer to a much-needed paradigm shift and the answers we seek.

Jeff Drake

2017

[1] Chalmers, Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness, 1995.

[2] Wikipedia.

[3] “A paradigm shift, as identified by American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn (1922–1996), is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. … Kuhn presented his notion of a paradigm shift in his influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962).” (Wikipedia).

[4] Phenomenology is the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about some object. An experience is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the object) together with appropriate enabling conditions. (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

[5] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

[6] Smith, David Woodruff, Husserl, London-New York: Routledge, 2007.

[7] Husserl, Phenomenology and the Crisis of Philosophy, 1965.

[8] “In Husserlian phenomenology, the “transcendent” is that which transcends our own consciousness—that which is objective rather than only a phenomenon of consciousness.” (New World Encyclopedia).

[9] “Intersubjectivity is a term used in philosophy, psychology, sociology, and anthropology to represent the psychological relation between people. It is usually used in contrast to solipsistic individual experience, emphasizing our inherently social being.” (Wikipedia).

[10] “If I think about a piano, something in my thought picks out a piano. If I talk about cigars, something in my speech refers to cigars. This feature of thoughts and words, whereby they pick out, refer to, or are about things, is intentionality. In a word, intentionality is aboutness.” (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

[11] “Embodied cognition (or the embodied mind thesis), a position in cognitive science and the philosophy of mind emphasizing the role that the body plays in shaping the mind.” (Wikipedia).

[12] An ancient tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart and spear throwing. (Wikipedia).

[13] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

[14] The Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty, 1962 (English translation).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception and Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics, 1964.

[17] Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 1962,

[18] Wikipedia.

[19] Scientific American article, Out of Our Heads, by Alva Noe, 2009.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Wikipedia.

[23] Wikipedia, The Extended Mind, Chalmers, 1998.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of substance — the physical kind — there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties and mental properties.” (Wikipedia).

[26] Wikipedia.

[27] 1

Chalmers, Panpsychism and Panprotopsychism.